Except as punishment

June 19, 2022

Juneteenth, a federal holiday as of June 2021, commemorates the end of slavery in the United States. Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st, 1863, but actually enforcing the end of slavery in the Confederacy depended on the progress of Union troops through the south, and thus General Gordon Granger’s General Order No. 3 on June 19th, 1865 freeing the slaves of Texas is held to be the “true” end of slavery.

Did slavery end there? Well, no; the Emancipation Proclamation only applied to states that had seceded from the union. It wasn’t until the 13th ammendment to the Constitution was ratified on December 6th, 1865 that slavery was truly illegal in the entirety of the United States. According to the standard narrative of American history that I was taught in school, that was the end of it - while black Americans would continue to suffer from violence and injustice, the 13th ammendment had at the very least ended the bondage of slavery.

The problem is: the 13th ammendment has a pretty major loophole. Here is the precise language of the statute:

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Slavery, part 2

It doesn’t take too much imagination to guess how this loophole could be exploited by someone truly committed to preserving the institution of slavery, as were many white southern landowners following the Civil War. They used their control over local government and law enforcement to target vulnerable black people with so called “black laws” that punished crimes like vagrancy and petty theft with lengthy prison sentences. They then leased their prison population out to private businesses like plantations, mines, lumberyards, and so forth.

Some examples of black laws used in this manner:

- Vagrancy laws required black people to submit proof of employment every year under penalty of fines or prison

- Children of impoverished black parents were taken into custody by the state and sold into “apprenticeships”

- “Sunset laws” imposed dramatically harsher fines or even prison sentences for minor infractions like loitering or swearing after dark, leaving it to local police to report when a particular arrest occurred

- “Pig laws” imposed harsh fines and prison sentences for theft of livestock, while simultaneously regulations on commerce made it difficult or impossible for black farmers to acquire livestock legally

Conditions for prisoners leased into hard labor were every bit as brutal as slavery, if not worse. Slave owners have some incentive to provide their slaves with a minimal standard of living, if for no other reason than to protect their investment. A plantation or mine owner that leases prisoners from the state has no such incentive.

Debt peonage

The major downside of a convict, from the perspective of a business owner seeking nearly free labor, is that the convict’s sentence eventually expires. So southern states used debt to ensure that the bondage would become effectively permanent.

Many of the infractions criminalized by black laws carried fines, and most freed slaves were quite poor and unable to generate significant income due to regulations designed specifically to exclude them from commerce or property ownership. To cope with the debt, poor black people would have little choice but to seek financial help from a wealthy white business owner, who therefore had enough leverage to force the debtor into an indentured servitude relationship. The threat was compounded by the fact that most black people were uneducated and illiterate since educating slaves was strictly forbidden during the era of slavery. So they were forced to sign draconian employment contracts that they couldn’t even read.

Debt peonage extended well into the 20th century. The federal government criminalized the practice, but for decades the Department of Justice’s standard practice was to refer debt peonage cases to local law enforcement which had a vested interest in perpetuating the system. And of course it was not hard to drum up criminal charges against debt peons for minor or possibly non-existent transgressions, allowing the new wave of slave holders to use slavery as a defense against prosecution!

So when did slavery end?

The Emancipation Proclamation and the 13th ammendment were without a doubt significant legal milestones in American history, but it is impossible for an honest reading of history to conclude that slavery faded away in the decades following the Civil War. The real end to the system would have to wait until World War II.

The question of whether or not America should join the war effort was highly controversial in the early 1940’s, before the attack on Pearl Harbor. President Roosevelt believed that war was inevitable and was quietly beginning preparations; as part of this effort he asked his advisors to predict what the Axis powers would use as propaganda against America. America’s treatment of its black citizens emerged as a leading contender.

On December 12, 1941, Attorney General Francis Biddle issued Circular 3591, a directive to federal prosecutors compelling them to prosecute cases involving involuntary servitude. He wrote:

Open force, threats or intimidation need not be used to cause a person to go involuntarily from one place to another to work and to remain at such work; nor does evidence of kind treatment show an absence of involuntary servitude.

In the United States one cannot sell himself as a peon or slave – the law is fixed and established to protect the weak-minded, the poor, the miserable. Men will sometimes sell themselves for a meal of victuals or contract with another who acts as surety on his [sic] bond to work out the amount of the bond upon his [sic] release from jail. Any such contract is positively null and void and the procuring and causing of such contract to be made violates these statutes.

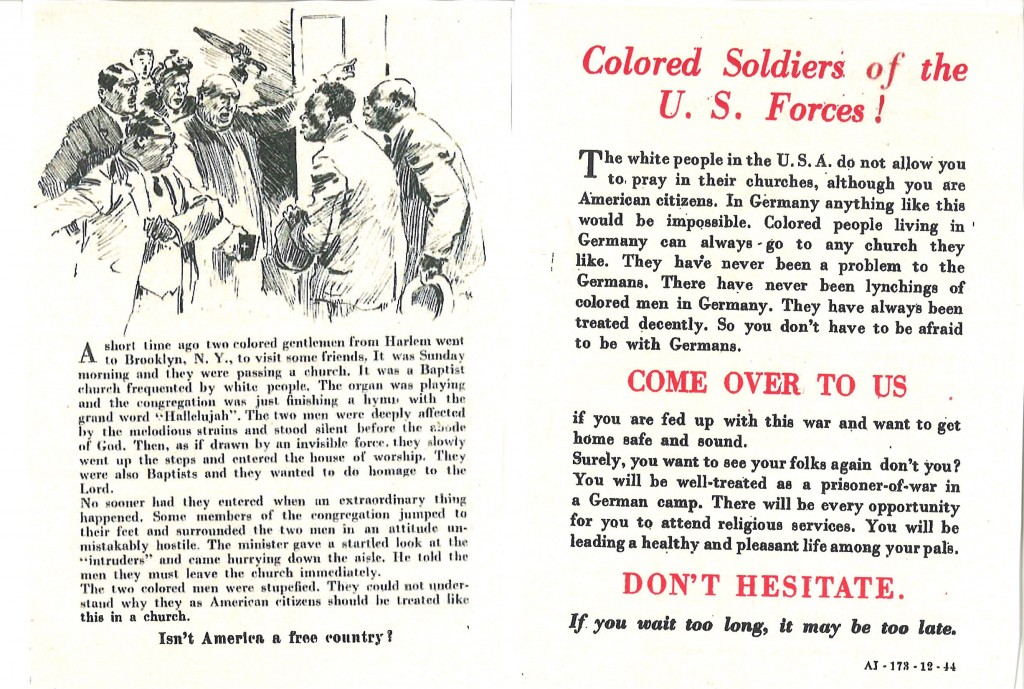

This, and subsequent prosecutions, marks the true end of slavery in America. Incidentally, the Roosevelt administration was right to worry about the propaganda threat; below is a leaflet distributed by the Nazis aimed at undermining the resolve of black American soldiers:

The full legacy of slavery

Learning about this history was, for me, rather jarring and disorienting. Americans held slaves during my grandparents’ lifetimes - anyone who is over the age of 80 at the time when I am writing these words coexisted with slavery in America. Some comments about the legacy of slavery in light of this observation:

- It has been said (I don’t know by whom) that “Hitler gave racism a bad name”; one can’t help but wonder how long slavery would have persisted were it not for the wartime propaganda effort.

- The impact of a law cannot be separated from how it is enforced.

- The most blatant black laws were all struck down following the Civil Rights act, but the technique of oppressing and exploiting people by over-criminalizing minor infractions lives on to this day.

- The project of uncovering white supremacy embedded in law and law enforcement is called “critical race theory”, and it should be taught in American schools.

References

- This history is recounted in detail in the book “Slavery by Another Name” by Douglas Blackmon. I have not read the book, but I’m pretty sure it influenced many of the resources that I consulted when writing this post.

- That said, I gleaned much of the WWII history from Blackmon’s essay “The World War II Effect”.

- I learned about some of the specific black laws by perusing the book “Wheel of Servitude” by Daniel Novak.

- I like the Youtube video “The Part of History You’ve Always Skipped” on the channel Knowing Better, which has additional references.